I had the opportunity to work as an assistant archivist when I was working on my MA in Chicana/o Studies at CSUN. During this time, I learned the importance of archives in the interpretation of history, especially Chicana/o history. Also, I learned how archives can be used to develop a counter-narrative of Chicana/o history in the United States. The goal of the counter-narrative is to challenge our understanding of the “truth.” And for many Chicana/os, we struggle how to expose the Chicana/o community about the “lies we were told” about our history.

My mentor, Rodolfo F. Acuña points us to the following strategy, by understanding “Chicana/o history as part of Chicana/o studies differs from Chicano history. Chicano studies history is political…. It recognizes that objectivity is a weapon used by those in power to control the “other.” The aim of Chicana/o studies history is not to reinvent another reality, but to seek to find facts that challenge Eurocentric interests.” (Truth and Objectivity and Chicano History, 3)

Clearly, writing history is political. As we seek out the “facts” to develop our counter-narrative, we are expose to the politics of interpretation. One very important lesson, I took away from being an archivist is the drive to connect all the dots in the story of our history, not just using the archives but connecting to the community involved in this history.

The following article is by Rodolfo F. Acuña, which discusses the current politics of interpretation in writing Chicana/o history:

Studying History In Translation

As we distance ourselves from the sixties, more and more Chicana/o monographs and dissertations are being written in translation. Many of the young scholars have never been involved in the civil rights movement, and much of what they write about the past is hearsay. Like any other second hand narrative, it becomes distorted over time, and myths about the past become accepted as truths.

The writing history is much like a literary translation; it relies heavily on the craft and integrity of the historian.

In the field of literature, the translation of foreign literature is an art. It is no easy task, and the best linguists have problems with quality translations. It is not so much getting the meaning of the words correct, but the translator’s ability to produce an equivalent target-language text. Also while a good translation depends on the interpreter’s knowledge of the source-language, it is also important for him/her to have a grasp of the subject matter translated.

Most of us have gone to the movies and watched Spanish language films with English subtitles. The experience can be distracting. Understanding both languages, you pick up the errors in the translation that confuse the plot. The more you know the languages, the more distracting a bad translation is.

No getting around it, translators shape our understanding of the story.

The writing of history is similar to translation. A person is not born a historian; the historian is more than what a colleague of mine calls a cuentista – a storyteller. She interprets history and that takes training.

I was a history major on my journey to a BA and an MA, specializing in U.S. history. When I enrolled in a doctoral program I switched to Latin American Studies. I wanted to work with Manuel Servín and Donald Rowland (a Bolton scholar). Manuel was a taskmaster; at the time he was the editor of the California Historical Society Quarterly.

Servín insisted that his seminar students not begin their research without exhausting the secondary sources. It was before the computer so you spent hours in libraries and poured over the catalogs and the bibliographies at the end of books. You did not have online book vendors so you haunted bookstores – no Starbucks; so you lugged a huge briefcase with thermos bottle full of coffee.

When you reached the point that you started researching primary sources, you pretty much knew the context, and you could form probative questions. In turn, you searched for documents in state archives, newspapers, and interviewed the experts in the field. Consequently, your research shaped your hypothesis – not the other way around.

My study was on the Age of Reform in Sonora, Mexico. As Lesley Byrd Simpson’s Many Mexico underscored, there is no generic model for all of Mexico. It followed that you could not learn the subtleties of 19th century Sonora by sitting in the Bancroft, the Huntington or the University of Arizona Libraries.

Gaining this background was costly in terms of time. I was married and a high school teacher, and active in the Latin American Civic Association and the Mexican American Political Association. There were no sabbaticals or financial assistance. So I would drive to Hermosillo, Sonora on a three-day weekend in search of Francisco Almada, Eduardo Villa and Laureano Calvo Berber – the leading Sonoran historians at the time — whose works I almost memorized.

I would stop in places where Ignacio Pesqueira, the governor for most of the Age of Reform, operated out of. Manuel insisted that I acquaint myself with the landscape. I kept in mind the words of the Prince, the protagonist in Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard (Il Gattopardo), who said that to understand the violence of Sicilian society; you had to understand the harshness of the land.

I have stored much of the research on The Sonoran Strongman in the CSUN Library, but it is difficult to replicate my thoughts of the places I visited, and my conversations with Mexican scholars. As much as I learned, given what I know today, if I had to rewrite the work it would be a different book. As in the case of translations, history should be continuously crafted.

Given this background, I am impatient with some of today’s scholarship. Although it is well funded – it often takes me ten minutes to read the acknowledgements to Ford and the like. Unfortunately this generous funding has not kept some of the history from being bad translations.

I just reviewed an excellent book – one of the best researched that I have read. However, the author had very little sense of place. Los Angeles like Mexico is very complex, and Chicanas/os often reflect where they live. East LA is not South Central or, for that matter, the San Fernando Valley.

I appreciate the importance of documents and oral interviews and everything that goes into a research project, but what has helped me most in interpreting documents has been life experiences. I have been a soldier, janitor, worker, a shop steward, a teacher, and an activist for over sixty years. I have made it a point to know almost every major Chicana/o leader. They honed my interpretative skills.

In today’s world it is assumed that if black or brown scholars write about their people that they are experts, which is not always the case. Through no fault of their own, some may not have the life experiences to be able to interpret the facts any better than white upper middle class professors. Some Chicana/o scholars go from K-20 without spending much time in the barrio, studying faces, or being involved.

As I mentioned in previous blogs, I am concerned that some of the historical works appearing on César Chávez and other movement figures are filled with half-truths, which are then cited to prove the author’s thesis or better still biases.

For example, recently several dissertations have appeared mentioning the Chicana/o Studies department at California State University Northridge. Usually I try to ignore the moscas (flies) – but no one likes cheap shot artists or liars. Moreover, the works are examples of shoddy research which will ultimately hurt our cause.

UCLA is 21 miles from CSUN, USC is 32 miles, and Hermosillo, Sonora is over 500 miles. It would seem to me that “scholars” writing about CSUN would have professionalism to interview someone from CSUN. At the very least their committee members should be professional enough to insist on accuracy. The CSUN Chicana/o studies department has 27 fulltime and over 40 part time faculty members – they are not hard to find. I am always available, and have an open door policy.

If a scholar has an axe to grind, he or she should at least know the facts or admit his/her biases. Biased works compromise the integrity of what we call Chicana/o history.

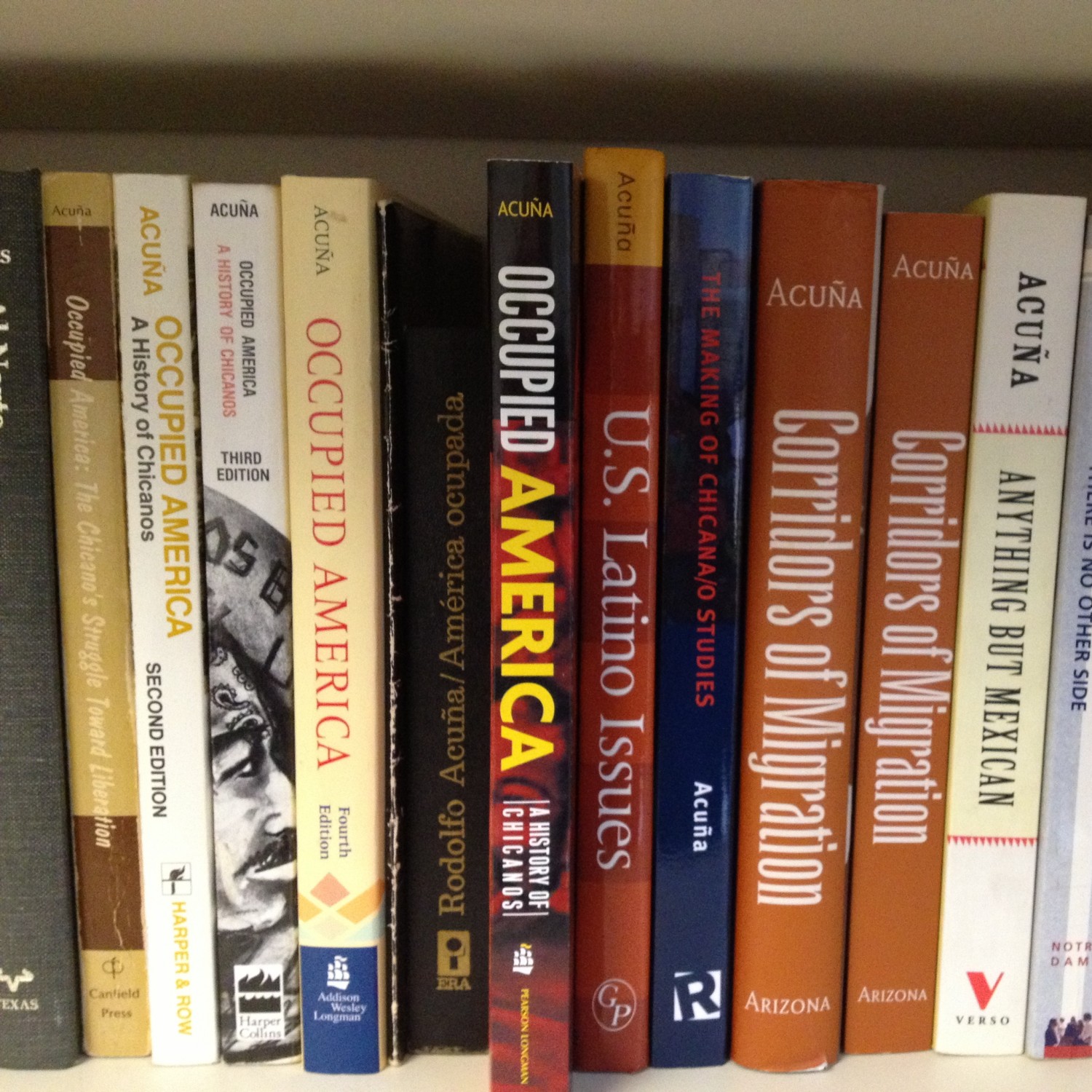

In over forty years I have published 22 books. I have been criticized because of my interpretation of the Mexican American War — according to some scholars; I lied because I wrote that the United States invaded Mexico. The truth be told, I always make sure that my documents are vetted and that they are used as evidence of what I say.

Everyone understands the differences between political and personal criticism. But what happens when the historian or scholar has no regard for the truth and tries to prove his or her biases at any cost? What happens when the author has a distorted and perverted mind?

Then false assumptions become history. Unlike on the streets, the translator gets off without reproach, and the movement suffers, which is tragic because the scholar has never been part of it – just cashed in on it – for proof, read the prefaces to their books and follow the money.