“The role of Chicana/o Studies is to organize and systemize the knowledge of people of Mexican descent, as well as to serve as a pedagogical tool to educate and motivate.”

Rodolfo F. Acuña, The Making of Chicana/ Studies, xxi

As we end the year, I reflect on the opportunities I have received this year. One of them was to present on the importance of Acuña’s Occupied America in Chicana/o Studies and History at the annual NACCS Conference in Chicago. This panel would not have happen without my conference booking agent, my brother Jose G. Moreno. Thanks for the opportunity!

My short presentation was titled, Searching For Chicana/o History: A Reflection On Dr. Rodolfo F. Acuña’s Occupied America And Archives. Here is the rough draft of the presentation. I hope you enjoy it!

Today discussion plays an important part in our struggle for liberation. And yes, I said liberation! As we sit here reflecting on the impact of Occupied America inside and outside of the ivory tower. There is a war-taking place throughout the United States and we (Chicana/os and Latina/os) are still the target.

The attacks toward us in Arizona, Alabama, and elsewhere are not new. Since the construction of US/Mexico Border in 1848, we as a community have faced decades of discrimination and attacks! Those attacks have made us stronger and has created a collective memory of struggles. So in this context, Dr. Acuña’s Occupied America was written.

For me, I share the 40 years history with Occupied America due to being born in 1972. But it was not until 1993, that I was introduced to his writings in my first of many Chicano Studies classes. And believe me, I taken many classes, which I have earned three degrees in Chicano Studies.

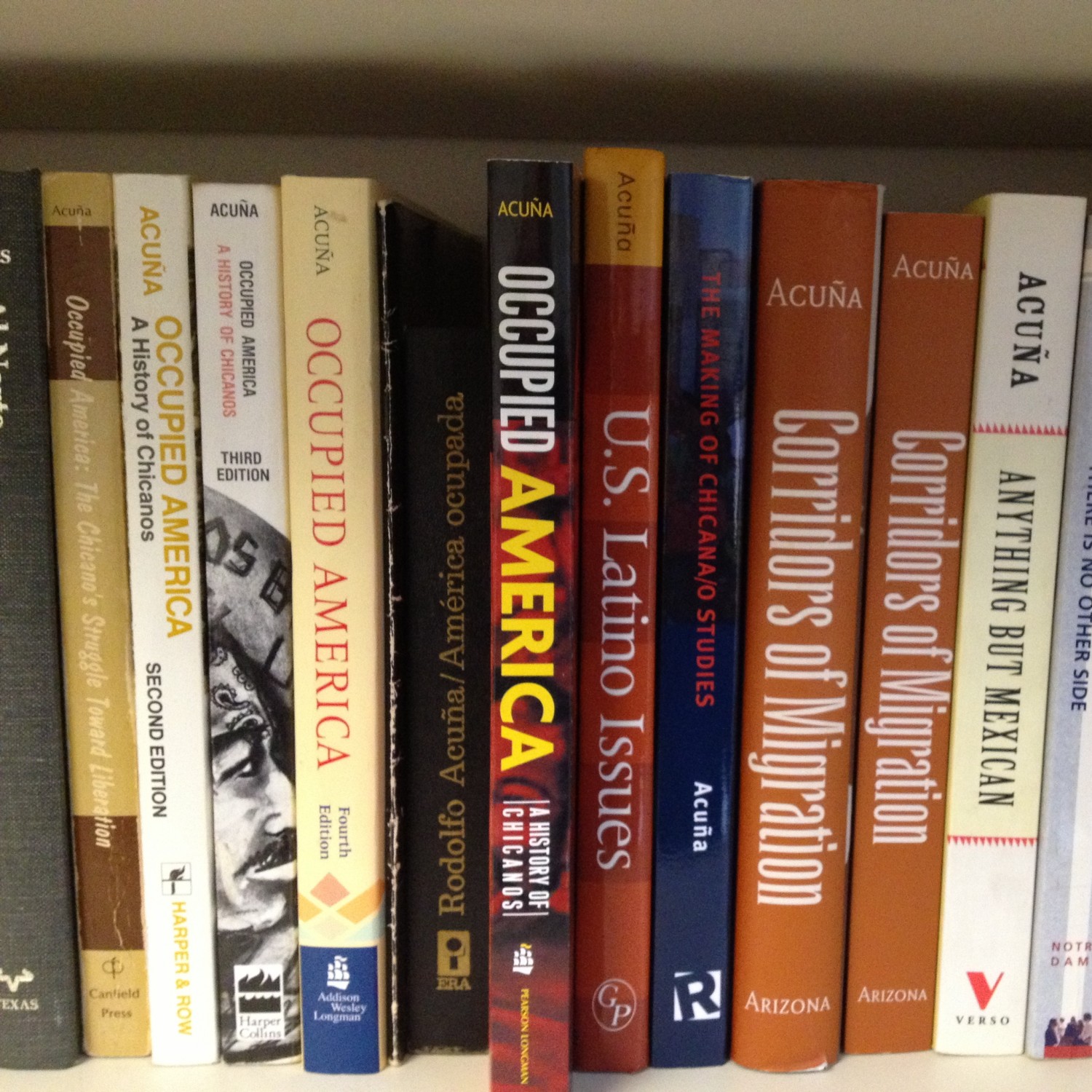

Throughout the last 40 years, Occupied America has gone through much revision by expanding the story. For some of us, we return to Occupied America, First Edition were he argues, “that Chicanos…are a colonized people.” And he is “convinced that the experience of Chicanos…parallels that of other Third World people who has suffered under colonialism.” Just like that, in the first few pages of Occupied America, First Edition, he introduces us to colonialism and connect us to the larger struggle against imperialism in the world.

But by the Second Edition, he returned “to the basics and collect[ed] [the] historical data.” Making “this version of Occupied America reflect[ing] [his] current understanding of the history of Chicanos.” He pointed out that, “all research must be put into the context of the historical process.”

In the following editions after one and two, he continued to re-examine the historical process by expanding the narrative of the story. By doing that, making each editions different from each other or he would say “less imperfect that previous one.”

It is important to mention and give credit to Dr. Acuña and Occupied America, First Edition, which challenged the “Frontier Thesis” of borderland scholars and history by addressing race, class, and later gender in the development of the West (or the Southwest). He addressed the “legacy of conquest” years before the movement of “New Western History” in the late 1980’s. And I believe without Occupied America, First Edition, you would not have the works of Limerick, Weber, and other borderland scholars. But that is a story for a different discussion or panel.

Moving forward, my presentation will focus on my experience on organizing Rodolfo F. Acuña Collection at CSUN by reflecting on my search for Chicana/o history through his archives and Occupied America. The overall goal is to highlight the importance of archives in the writing of Occupied America.

I began this story in 2004, when I was a graduate student in Chicano Studies at CSUN. As, I was waiting for a class; I came across a flyer announcing that the Urban Archives Center was looking for interns to help in the processing of Dr. Acuña Collection. So like any other graduate student, I decided to add more work to my life and took on an internship at the center. And I guess the reason I took on the task is to gain a better understanding of the historian craft and Chicana/o history. But the real reason, I wanted to see or find the sources of his writings, especially Occupied America.

And for the record, the task of processing his collection would not be easy due to being composed of more than two hundred boxes! For being a historian, he decided to save mostly everything he collected in his career as activist-scholar. For me, I took on task of processing his collection by taking on the role of a detective. In this role, I began to search every boxes looking from the evidence or connection to Chicana/o history!

As time want on, I came across numerous archives, like the Paul Taylor Collection and the Federal Writers’ Project, which focused on farm labor and strike of the 1930s. Also, he saved numerous journals, newsletters, and newspaper, like La Gente de Azltan, El Popo, and La Raza Magazine. But the most important find for me was an original draft of Occupied America. I was amazed that I found the draft but I was shocked that it was typed on yellow notebook paper! Yes, yellow notebook paper!

During the three years of processing his collection, I moved from an intern, to a graduate archivist, and at the end was an assistant archivist. In this time, I also came to realize that every historian is archivist and every archivist is a historian. The overall experience of searching for Chicana/o history among his archives gave me a stronger link to our collective history. In this sense, I came to understanding through his archives and Occupied America the importance of the historical document in the narrative of Chicana/o history.

So, I end this presentation with the following statement, they can ban our books but they cannot destroy our collective memory or knowledge of our community. The time is now to FIGHT BACK!

c/s