“Public histories provide meaning to places.”

David Glassberg, Sense of History, 18

Being an academic migrant, I always find myself searching for a sense of place, the feeling of home. Home is the location of your childhood or family memories. For me, this place is La Colonia, especially Bonita Avenue.

The following is an excerpt from my manuscript (rough draft), Searching for Memories in La Colonia: Migration, Labor, and Activism In Oxnard, California, 1930-1980, focusing on my mother’s life in La Colonia.

Throughout the years, I have had many conversations with my mother, Gloria about her life growing up in La Colonia. She has shared stories of migration, culture and community. Her understanding of these experiences shaped her identity as a Mexican. In this post, I share my mother’s reflection on growing up in La Colonia through her interaction with her family and community.

My mother, Gloria was born in 1952 in a one-story house in the Colonia Village’s housing project on Bernarda Court in La Colonia. Her father Carlos was a packinghouse worker and her mother Margarita was a housewife. She was the second child of Margarita and Carlos, whose family included two more children from a previous marriage. In 1956, she moved from the housing project to her grandfather’s house on Bonita Avenue.

My mother attended grammar school in La Colonia; Ramona School is only four houses down from her home. Juanita School is only two blocks away. It was not until the mid-1960s, that she attended a school outside her neighborhood. In 1970, she graduated from high school and one-year later she married my father, Louie.

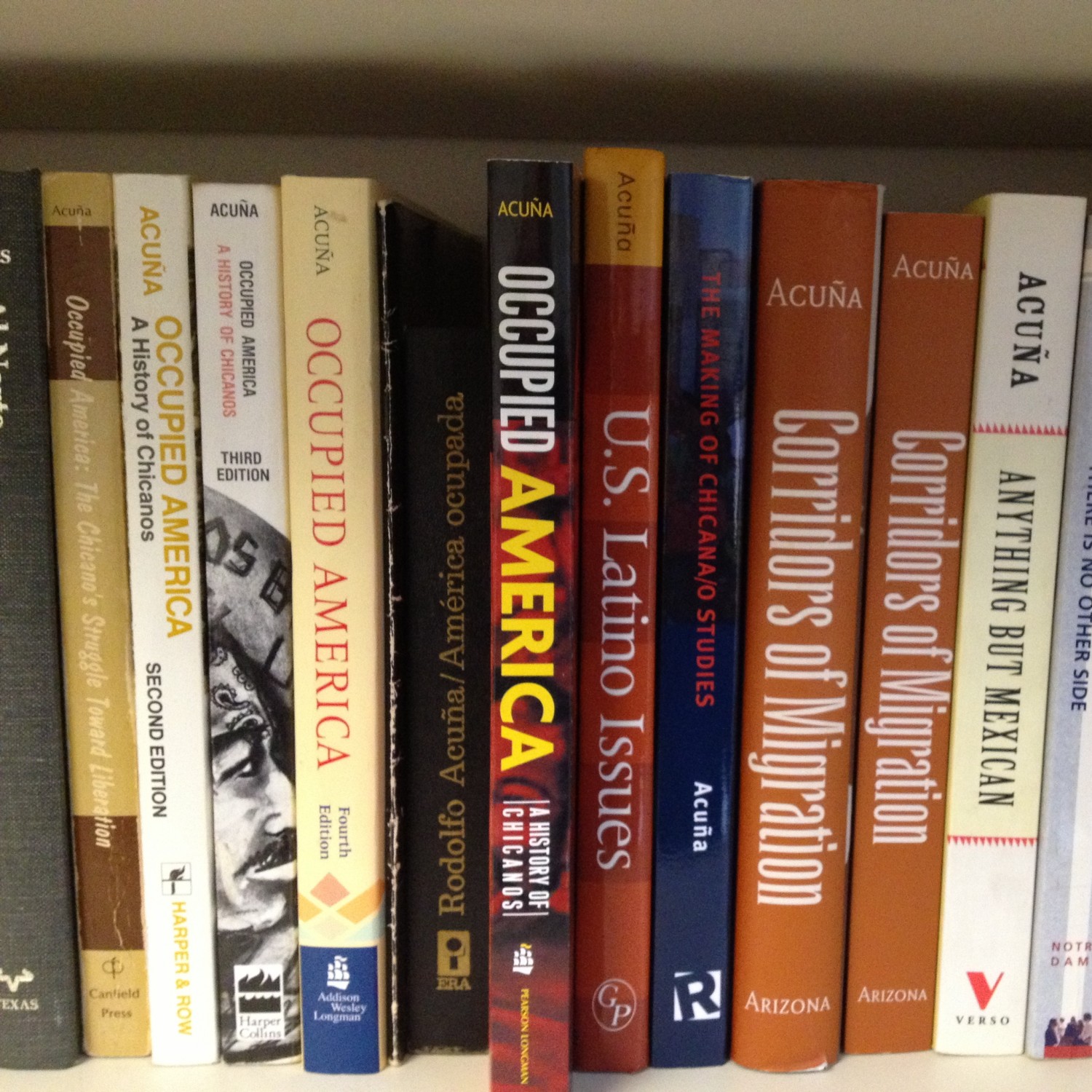

Her understanding of culture, migration, and community has shaped her identity. Historian Juan Gómez-Quiñones states “culture is learned rather than ‘instinctive,’ or biological.” My mother learned to identify as Mexican from her parents and community. Throughout her life, her Mexican identity has been questioned by American society because she does not “look Mexican” due to her light skin, freckles and reddish hair.

During one conversation with my mother, I asked her the following question: have you been treated differently due to the color of your skin? She responded with the following story; as a child, she recalled going to events in downtown Oxnard with her grandfather, Jose. Individuals at those events would ask her grandfather if he was baby-sitting her. Their remarks frustrated her grandfather for they did not just come from Whites, but also from Mexicans. Listening to those comments introduced my mother to how people in the United States use skin color to define race, ethnicity, and nationality.

Eventually, my mother came to an understanding that many people do not see her as being Mexican. But she explained that the color of her skin did not make her Mexican, instead her history and her community did, and for most of her life, she has lived in La Colonia. Her neighborhood has influenced her culture and her history, shaped by many generations of migration.

This discussion of a family history and of migration does not have an ending. Growing up in La Colonia has affected the way my mother sees herself and the way she has raised her sons. In her heart and mind, the little house on Bonita Avenue has always been home and community to her, no matter if she did not live there. Those experiences have defined my mother’s life. She sees the world differently now. She sees the need to be a defender of her community, an activist who informs her community about their human and civil rights. My mother continues to play a role in supporting and participating in the struggle to end the brutalization, marginalization, and segregation of the Mexican community in Oxnard, California.

It is essential to mention, it was a sad day for my mother on September 2012, as she turned off the lights and closed the door knowing she would never return to her grandfather’s house again. But it was time to move on after years of personal struggles with numerous family members over the direction of the property.

In the end, my mother took with her the memories of struggles, happiness, and love. And no one can take those memories anyway!

c/s