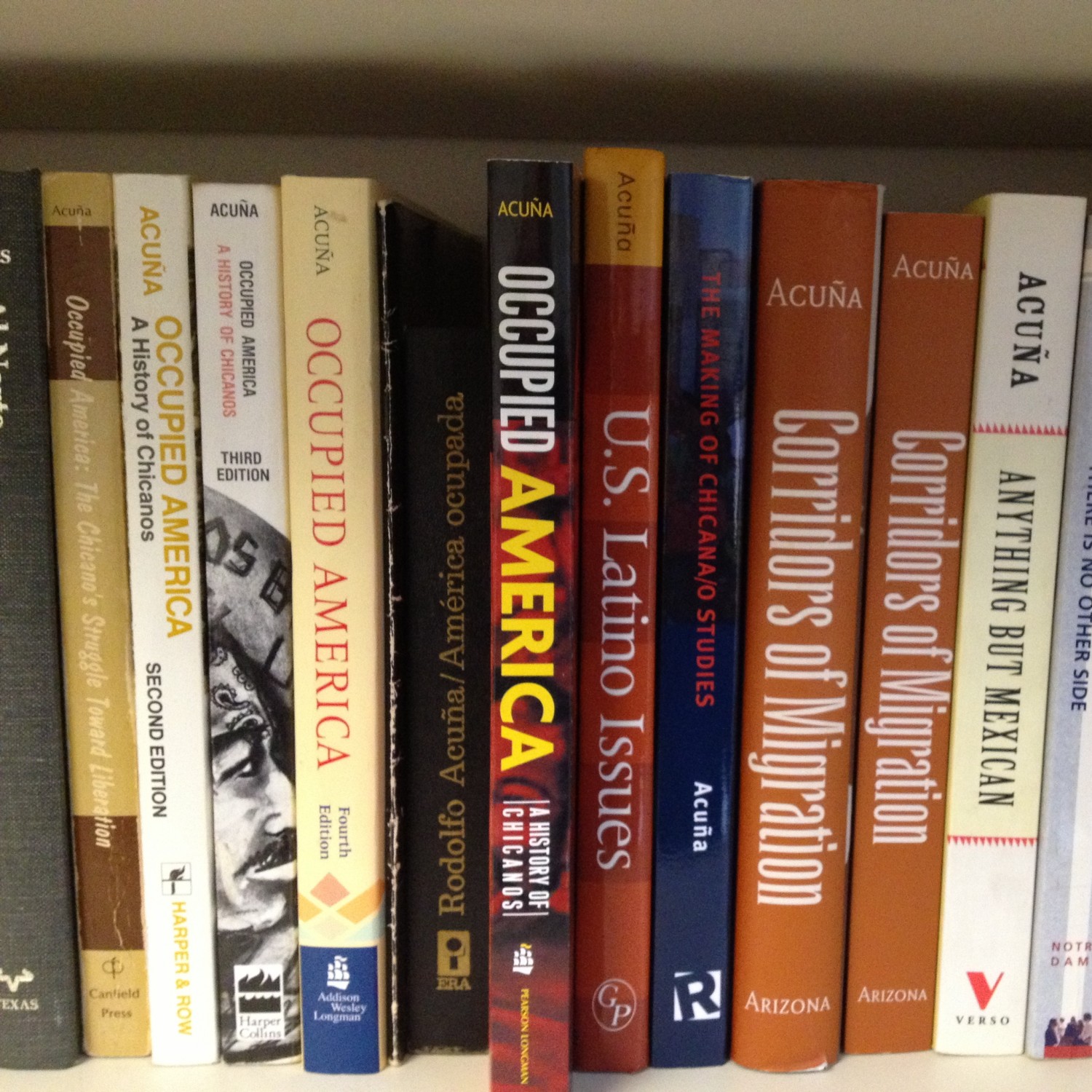

The majority of the students at Ramona School were Mexican and Black, 1963. Courtesy of the author’s family collection.

The following is an excerpt from my manuscript (rough draft), Searching for Memories in La Colonia: Migration, Labor, and Activism In Oxnard, California, 1930-1980, focusing on the struggles to end school segregation.

“Education Yes, Segregation No.”

Al Contreras

Second-Vice President of the Ventura County Community Service Organization

“Oxnard had a segregation problem, but the board’s response was to ignore it.”

Harold De Pue

Former Superintendent of the Oxnard School District

On May 17, 1954, the United States Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education concluded, “that in the field of public education, the doctrine of ‘separate-but-equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” School segregation was now unconstitutional. The following year, the Supreme Court delegated the task of enforcing desegregation to the lower court with “no judicial guidance on remedies” but, it allowed school boards and districts to move forward “with all deliberate speed.” What followed after Brown was several decades of protests and court cases over desegregation. The effects of deliberate speed did not just impact Black children, but also Mexican children in the Southwest, especially in Oxnard, California.

Before, Brown, Mexican parents were engaged in struggles to end school segregation in Southern California with Alvarez v. the Board of Trustees of the Lemon Grove School District (1931) and Mendez v. Westminster School District (1947). Both court cases ruled that the segregation of Mexican children was unconstitutional. Those court cases influenced a generation of Mexican parents, organizers, lawyers, and teachers to fight for educational justice. As a result, the Mexican working-class community of Oxnard is connected to this legacy of educational activism.

By 1963, seventeen years after Mendez and nine years after Brown, which ruled that the segregation of students-of-color was unconstitutional, the Oxnard-Ventura County National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Ventura County Community Service Organization (VCCSO) and other organizations came together to advocate for the desegregation of the Oxnard School District (OSD). Those struggles led to mass protests on the issues of racial discrimination and de facto segregation within the city of Oxnard.

This article belief examines the struggles to end school segregation between 1963 and 1974 by focusing on 1963 School Bond issue through the 1970 Soria v. Oxnard School District Board of Trustees case.

1963 School Bond

The Oxnard School District had laid down the foundation of segregation during the 1920s when they utilized de facto policies to segregate Mexican children from White children. As the Mexican population increased in Oxnard during the 1930s and 1940s, the local school district moved to build neighborhood schools within La Colonia, the oldest Mexican neighborhood in the city. So, as the school district moved to develop their “neighborhood schools” concept, it would create Ramona School (1940) and Juanita School (1951) within blocks from each other in La Colonia.

Throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, the school district continued to expand Ramona and Juanita Schools due to the increase of the Mexican population. By January of 1963, the school district began a campaign for a new 3.2 million dollar school bond for the upcoming January 22 elections. The school district pushed for the school bond to reduce overcrowding and the construction of a new junior high school in La Colonia. The school district argued it would save $5000 a year on the transportation of over 300 children from La Colonia to another junior high school in the district. In response to the school bond, a support committee was formed composed of community individuals and organizations, which endorsed the bond. The VCCSO gave the school bond a partial endorsement but pushed for a different site for the new junior high school.

Source: The Press-Courier, 8 Jan 1963.

On January 17, school officials met with the VCCSO to sway them into pro-bond position. The organization opposed the bond on the grounds that it would create a segregated junior high school in La Colonia. VCCSO President, Cloromiro Camacho noted, “this is complete discrimination” and “if a school is built here, it would be 39 percent Mexican or Negro. Therefore, this is a segregated school.” The VCCSO was not against the construction of a new junior high school but just not in La Colonia. The school officials informed VCCSO that Superintendent Harold DePue “has vowed that he wanted to spend more money here [La Colonia] because the children need it more.”

On the same day, the local NAACP met and took an anti-bond position. The local NAACP stated, “we support quality education for all children of Oxnard, however, we cannot endorse segregation in any form.” Superintendent DePue stated his disappointment by the opposition of the school bond but “we must remember that the action taken by these groups is the right of any individual or group and it must be respected as such.” In a response to the anti-school bond position of the VCCSO and local NAACP, the editor of The Press-Courier took the position that there was no racial discrimination in the school district and that “opposition cares less for the welfare of the families of Oxnard and children.”

On January 20, the VCCSO kicked off their campaign against the school bond with the goal of getting a one hundred percent no vote in La Colonia. The VCCSO organized a house-to-house drive in La Colonia with pamphlets encouraging the residents to vote no on the school bond. Former VCCSO president, Tony Del Buono appealed to the executive board of the VCCSO to “approve the bonds but oppose the site because of de facto segregation.” A similar comment made by a former city councilman, Harold Nason called on the VCCSO to “support the bond issue for all children and then oppose the construction site if they want to.” The school bond caused tensions among the membership of the VCCSO. In the past, the VCCSO had supported the previous school bonds. Camacho defended the position of the VCCSO and “as for many members of our group that will not join us in opposition, we respect them and their democratic right of vote and freedom.”

On January 22, Oxnard’s voters went to the ballot to vote on the school bond, which included a new junior high school in La Colonia. Voters approved the school bond with a yes vote of 71.9 percent. The school bond won 9 of 14 precincts but lost in the three La Colonia precincts, where VCCSO and local NAACP organized against the school bond. The editor of The Press-Courier continued its attack against the local NAACP and VCCSO by stating that the residents of La Colonia “were torn by misguided efforts on the part of two small groups to defend the bond.” The residents of La Colonia were divided over the location of the new junior high school.

Due to the opposition, the school district requested information from the California Department of Education over the matter; school officials wanted to know if there were any legal issues. The school board requested an external study on the question of de facto segregation. The local NAACP and VCCSO continued to believe that new junior high school in La Colonia would create de facto segregation. The local NAACP called on the trustees of the school district to organize a special meeting on the school issue.

By February 5, the school district informed the residents of Oxnard that they had been advised by Thomas Braden, president of the California State Board of Education to get a legal opinion before moving forward with the new junior high school in La Colonia. Barden stated, “it seems that the proposal would in effect create de facto segregation where it has not previously existed.” The school district agreed to seek a legal opinion from the District Attorney. Again, the local NAACP and VCCSO urged the school district to reconsider their plan for the new junior high school before they seek legal action on this matter.

The Press-Courier reported that the school district was composed of 51.4 percent of minority students, which broken down to 9.8 percent (Black), 38.8 percent (Mexican), and 2.8 percent (Asian). The data showed the majority of Mexican and Black students attended school in La Colonia compared with other schools outside of La Colonia area. At Ramona School, the breakdown was 71.9 percent (Mexican) and 23.2 percent (Black) and at Juanita School, it was 75.6 percent (Mexican) and 19.4 percent (Black). Furthermore, the data was used to call for desegregation of the school district.

On March 5, the local NAACP submitted numerous “anti-segregation” proposals to the school district for consideration. The proposals called for the desegregation of all schools in the district with new boundaries and pairing of schools. Althea Simmons, field secretary of the National NAACP stated that the abandonment of La Colonia site “would be the best solution to the de facto segregation problem.” The local NAACP called on the school district to adopt a “desegregation” plan. Simmons stated it was “necessary not only to eliminate racial segregation of minority group but also to eliminate alleged segregation of predominately white schools.”

On April 2, Ventura County District Attorney Woodruff Deem submitted a legal opinion on La Colonia school site to the school district. Deem stated, “it would be valid if the trustees went ahead after making an ‘exhaustive effort’ to study all facets of the racial problem in La Colonia area” but “urged trustees to consult freely with organization and community groups in seeking assistance to explore alternative.” Trustee president Mary Davis stated, “we’re right where we started,” with no solution on the issue. In a response to the legal opinion, trustee Robert Pfeiler suggested to form a community committee to address issue of de facto segregation. Pfeiler stated, “let the parents get together and talk it over and bring it all into the open.”

By April 16, the trustees announced an open community meeting set for April 30 at Juanita School to discuss the concerns of the overall community on La Colonia school site. More than seventy residents, which included members of the VCCSO and local NAACP, attended the special meeting and it was very clear that the community was spilled on the issue of La Colonia school site. It was reported by the Juanita-Ramona School PTA that at least 80 out of 100 residents in La Colonia surveyed supported the new junior high school. On the other side, VCCSO vice president, Leo Alvarez pointed out that the issues of de facto segregation among the school district are related to the racial discrimination within the housing policies of the city. The school district trustees reminded the residents that they would listen to their opinions but the final decision is on the school board. On May 7, the school board stated they came to a compromise on La Colonia school site and will announce the decision in two weeks. Trustee Pfeiler stated that the school district and residents of La Colonia, “can come to very sensible agreement” on this matter.

On May 21, the school board announced it would not use La Colonia site for a new junior school. Trustee president Davis stated that school district had to face up to the truth of the issue but “they were unaware of the idea of de facto segregation as deeply rooted problems until these organizations outlined their objectives at numerous meetings.” The school district would work on solving the issue of de facto segregation by moving “minority students” to other schools with space available and expand the size of the Fremont Junior High School. Fred Brown, local NAACP president stated that the decision not to build the new junior high school in La Colonia was “a great step toward in eliminating segregation problems in local schools.” Deep debate continued about the new junior high school in La Colonia. On June 18, local residents accused the school board of breaking their promise to build a new junior high school. In a crowded school board meeting on June 24, the school board took the position that they would not build a new junior high school in La Colonia. Trustee Dr. Thomas Millham stated, “I never realized the magnitude of the de facto segregation problem.” In not building a new junior high school, the school district still had issues over enrollment.

At the August 27 school board meeting, the local NAACP called for the integration of the Ramona and Juanita Schools in La Colonia. Fredrick Jones, vice president of the local NAACP stated that “segregation pattern do exist in those schools, and if the board would take a mature approach, the problem could be solved.” By September 3, the school board responded to the local NAACP proposal from the integration of all the schools in the district but especially La Colonia’s schools. The school district suggested calling for the opinion of parents of on this issue. In addition, the school district called on the State Commission on Equal Educational Opportunities to investigate claims of de facto segregation made by the local NAACP. The school district claimed, “they never have gerrymandered any boundary line” within the district.

On October 8, the school board rejected the local NAACP’s May 5 proposal to integrate the neighborhood school system. In addition, the school district would not build a new elementary school on La Colonia site. On November 19, the local chapter of Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) called on the school board to consider its recommendations to end de facto segregation within the district. The school district claimed that some of the recommendations were similar to NACCP request and others had been already put into effect within the district. CORE expressed that action on the recommendations needed to be done immediately, if not they would call for a mass demonstration at the next school board meeting in December. The school district addressed CORE’s recommendations in a letter, stating the “plans for the future include doing whatever appears appropriate and with our power to combat…de facto segregation.” By December 11, the school district announced that they were “in support of integrating Oxnard schools wherever it is possible and feasible and moved toward doing so.” Furthermore, the school district would consider a request by Superintendent De Pue and Richard Zanders of CORE to develop a plan to redraw school attendance boundaries to eliminate de facto segregation and a program to educate teachers & administers about minority students.

1970 Soria v. Oxnard School District Board of Trustees

After many years of false promises from the school district over the issue of de facto segregation, the Mexican working-class community finally took a major stand. On February 26, 1970, a class action lawsuit on the behalf of students at Rose Avenue, Juanita, and Ramona Schools was filed against the school district and trustees seeking a prompted desegregation and restoration of racial/ethnic imbalance. Trustee Kane responded to the lawsuit by stating “it’s a disappointment that they (plaintiffs) don’t agree with us that our effort is a substantial one.”

A class action lawsuit was filed in the United States District Court, the Central District of California on the behalf of Debbie & Doreen Soria and other students of color. The lawsuit alleged that the OSD’s Board of Trustees “had consistently maintained and perpetuated a systematic scheme of racial segregation by capitalizing on a clear pattern of de facto racial segregation in Oxnard.” The plaintiffs accused the school district of violating their Fourteenth Amendment rights. Thomas Malley of Legal Service Association of Ventura County, Stephen Kalish, and Peter Ross of Western Center on Law and Poverty represented the plaintiffs. On the other side, Ventura County Assistant Consul William Waters represented the school district. The plaintiffs submitted evidence that the school district was divided by race; up to 96 percent of students of color attended school in the eastside compared to the 90 percent of white students attended school in the North Oxnard.

On January 5, 1971, a supporter of integration and key ally to the Mexican working-class community, Rachel Wong was elected to the school board. A hearing on the lawsuit was held on May 12, which the court granted the plaintiffs’ motion for summary judgment. Judge Harry Pregerson found that the school district failed or refused to adopt a desegregation plan. He issued an interlocutory order on the school district “to submit to this court within twenty (20) days a plan that promised realistically to work now so the racial imbalance existing in the Oxnard Elementary Schools is eliminated root and branch.” On May 25, the school board voted to seek a stay of motion on court order integration plan to the Ninth Circuit Court.

By July 21, the district court approved OSD’s desegregation plan and ordered immediately implement the plan. The desegregation plans composed of pairing schools and two-way busing of students. In August, Attorney Edward Lasher on the behalf of the school district filed a plea for a motion of stay on the court order integration plan in the Ninth Circuit Court. Supporters of the integration plan accused the school district of creating “an emergency in an attempt to bypass Judge Pregerson[‘s]” decision. Critics of the court-ordered integration plan formed the Citizens Opposed to Busing (COB), which focused on fighting the busing issue through legal channels.

In the countdown to implement the integration plan in September, the school district continued to wait for a decision on the motion of stay. Some non-supporters of the order integration decided to pull their children out of the school district. Dr. Keith Mason, trustee president publicly stated that he would remove his children from the school district if the motion of stay is not approved to stop the busing plan. Nancy McGrath of COB stated that “some parents have sold their homes and moved from Oxnard. Some who have stayed say they will educate the children themselves.” Two days before the opening of the 1971-1972 school year, there was still no decision made on the motion of stay by Ninth Circuit Court. Superintendent Doren Tregarthen announced, “we’ll go ahead and open school on schedule” and “the classrooms are ready, the teachers are ready, the buses are ready.”

OSD Report, Sept 1971. Source: OSD Archives.

On September 13, the school district opened the new 1971-1972 school year with a court-order integration plan that bused more than three thousand students to schools throughout the district. The Press-Courier reported that the first day of busing started “without the protests and violence that [are] ripping other cities.” Superintendent Tregarthen stated that the first day went smoothly and “underst[ood] the anxiety of the parents.” By September 14, the Ninth Circuit Court turned down the motion of stay to stop busing of students. The court stated that the school district “should have in the first instance presented its application for a stay in the district court” not the Ninth Circuit Court. Superintendent Tregarthen commented “that’s dumb, it’s a real copout” on the decision of the Ninth Circuit Court. Trustee Dr. Mason stated he believed the school district was “betrayed by the courts and will pursue the stay until we get some decent answers.” Even with the decision, the school district still had another appeal on the court-ordered integration in Ninth Circuit Court.

On August 21, 1972, the Ninth Circuit Court again denied a stay on the court-ordered integration. The school board voted four to one to appeal the court’s decision to the Supreme Court. The new anti-busing legislation led to debates over the ability to postpone or roll back early desegregation court cases. U.S. Chief Justice Warren E. Burger and William Douglas refused to grant a stay on the school district case. By late October, the Supreme Court unanimously denied the request for a stay on the court-ordered integration plan. On August 27, 1973, the Ninth Circuit Court ruled on the court-ordered integration. The school district argued that ethnic imbalance was created by population patterns of the city, not the school board. The Ninth Circuit Court found the district court’s decision as “inconclusive and vague on the question of the school board’s segregative intent.” The ruling remanded the case back to district court, which the plaintiffs needed to provide the evidence in determining if the school district had committed a constitutional violation. The ruling did not affect the court-ordered desegregation plan.

On December 10, 1974, the district court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs again. The plaintiffs’ lawyers were able to provide new evidence and a historical link of segregation by revealing the school board minutes from August 1934 through June 1939, which discussed the segregation of Mexican students from White students. In the previous, Ninth Circuit Court decision, it stated that the school district had never maintained a “dual school system” but the new evidence showed the school district had intent to racially segregate the district beginning in the 1930s through 1970s. The school district had developed segregation within the district by building two Mexican schools in La Colonia to limit the interaction of White and Mexican students. Previous Superintendent Richard Clowes (1949-1961) and Superintendent Harold De Pue (1961-1965) in court pointed out that the school board took no action on the segregation issues and had a “do nothing” policy. In the final summary, Judge Pregerson stated that the school district and school board failed to act to end segregation and the “remedial plan shall continue in full force and effect.”

The struggles to end school segregation left many different markers on the Mexican working-class community, the school district, and the city of Oxnard. The struggles gave the Mexican community the opportunity to speak up and defend the education of their children. Even more, those events inspirited a generation of local Chicana/o youth to join the Chicano Power Movement during the late 1960s and 1970s. As for the school district and the city, it exposed the evidence that city founders, growers, and city officials created a segregated city divided by race and class. As a result, of the increase of enrollment and economic crisis after 1974, the school district under the leadership of Superintendent Norman Brekke transformed into a year-round district.

The issue of busing continued into the 1980s, as a group parents organized themselves under the banner of the Parents For Neighborhood Schools demanding the end of forced busing. By 1987, Judge Pregerson removed the court-ordered integration. However, the school district still needed to maintain the racial and ethnic balance according to federal and state laws. As the demographics changed in Oxnard and elsewhere in California, the school district enrollment began to shift and since the beginning of the court-ordered integration in 1971 charged from 41 percent to 18.4 percent (White) and to 46 percent to 72.1 percent (Mexican) by the 1990s. As noted by Superintendent Brekke, it became “impossible any longer to have the kind of racial and ethnic balance we had in 1971. There are going to be classes that 100% Hispanic.” To conclude, the struggles of “Education Yes, Segregation No,” influenced a generation of Mexican children in Oxnard as their parents, organizers, lawyers, and teachers fought for educational justice.